In physics, the acoustic wave equation is a second-order partial differential equation that governs the propagation of acoustic waves through a material medium resp. a standing wavefield. The equation describes the evolution of acoustic pressure p or particle velocity u as a function of position x and time t. A simplified (scalar) form of the equation describes acoustic waves in only one spatial dimension, while a more general form describes waves in three dimensions.

For lossy media, more intricate models need to be applied in order to take into account frequency-dependent attenuation and phase speed. Such models include acoustic wave equations that incorporate fractional derivative terms, see also the acoustic attenuation article or the survey paper.

Definition in one dimension

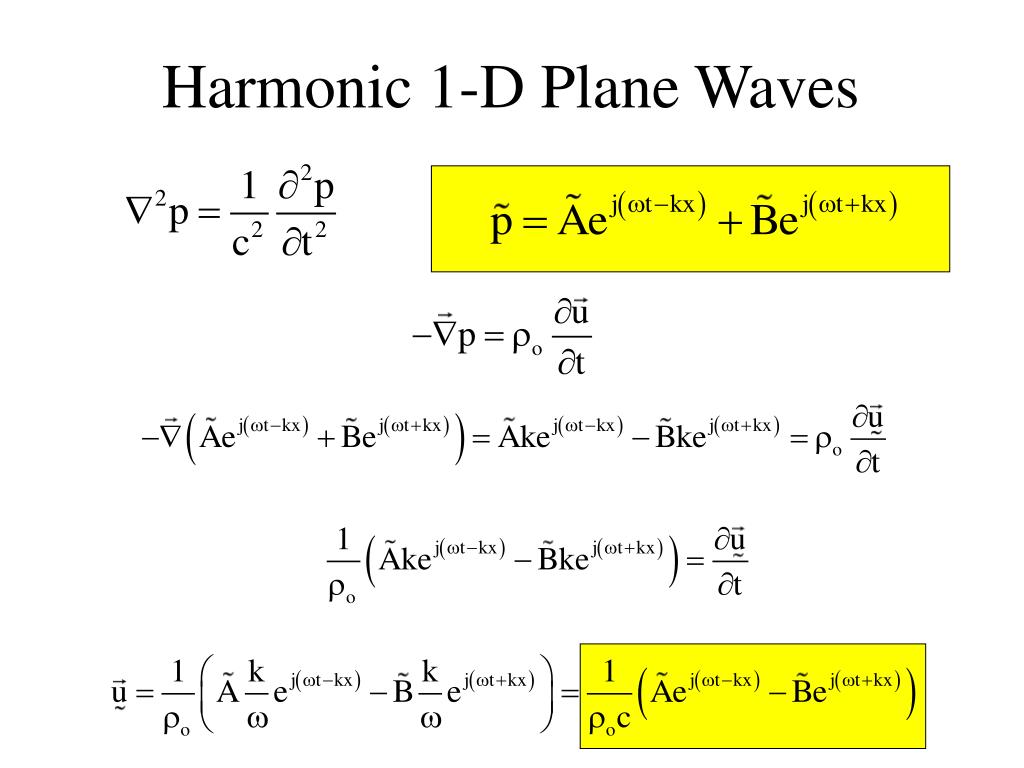

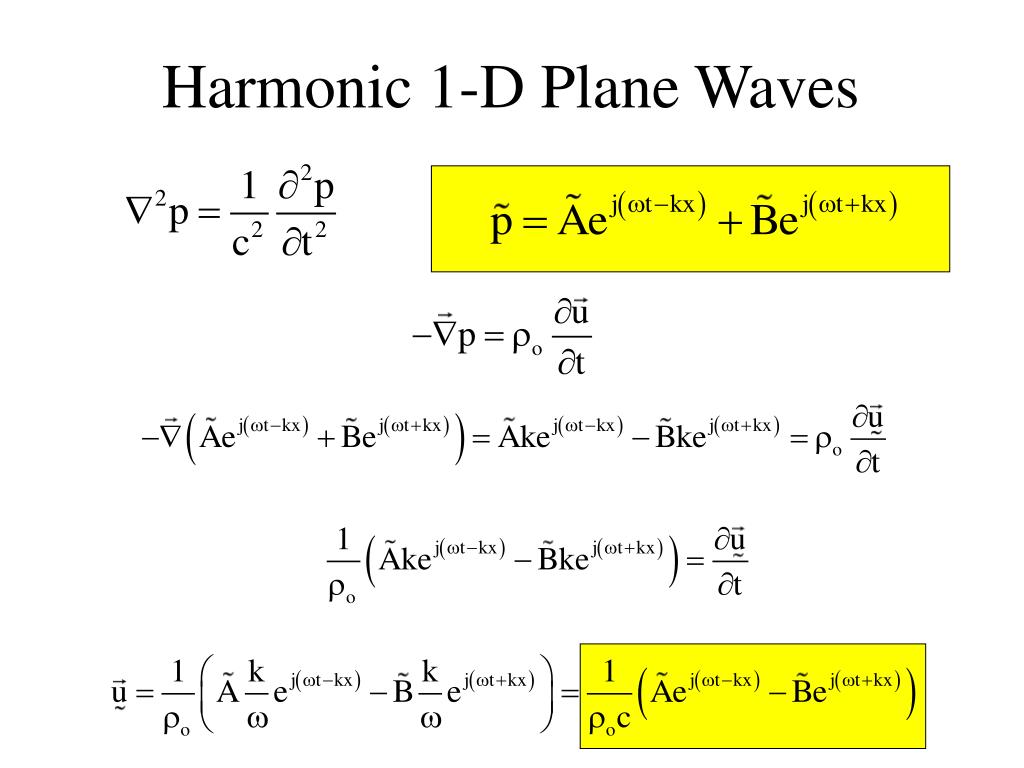

The wave equation describing a standing wave field in one dimension (position ) is

where is the acoustic pressure (the local deviation from the ambient pressure) and the speed of sound, using subscript notation for the partial derivatives.

Derivation

Start with the ideal gas law

where the absolute temperature of the gas and specific gas constant .

Then, assuming the process is adiabatic, pressure can be considered a function of density .

The conservation of mass and conservation of momentum can be written as a closed system of two equations

This coupled system of two nonlinear conservation laws can be written in vector form as:

with

To linearize this equation, let

where is the (constant) background state and is a sufficiently small perturbation, i.e., any powers or products of can be discarded. Hence, the taylor expansion of gives:

where

This results in the linearized equation

Likewise, small perturbations of the components of can be rewritten as:

such that

and pressure perturbations relate to density perturbations as:

such that:

where is a constant, resulting in the alternative form of the linear acoustics equations:

where is the bulk modulus of compressibility. After dropping the tilde for convenience, the linear first order system can be written as:

While, in general, a non-zero background velocity is possible (e.g. when studying the sound propagation in a constant-strength wind), it will be assumed that . Then the linear system reduces to the second-order wave equation:

with the speed of sound.

Hence, the acoustic equation can be derived from a system of first-order

advection equations that follow directly from physics, i.e., the first integrals:

with

Conversely, given the second-order equation a first-order system can be derived:

with

where matrix and are similar.

Solution

Provided that the speed is a constant, not dependent on frequency (the dispersionless case), then the most general solution is

where and are any two twice-differentiable functions. This may be pictured as the superposition of two waveforms of arbitrary profile, one () traveling up the x-axis and the other () down the x-axis at the speed . The particular case of a sinusoidal wave traveling in one direction is obtained by choosing either or to be a sinusoid, and the other to be zero, giving

- .

where is the angular frequency of the wave and is its wave number.

In three dimensions

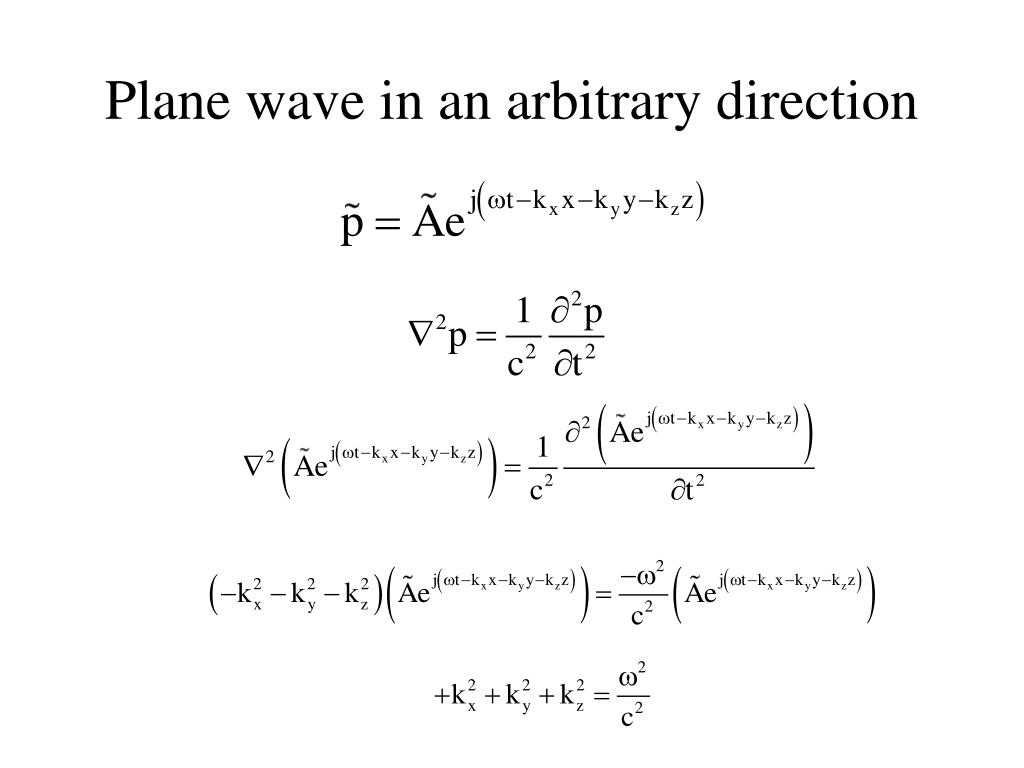

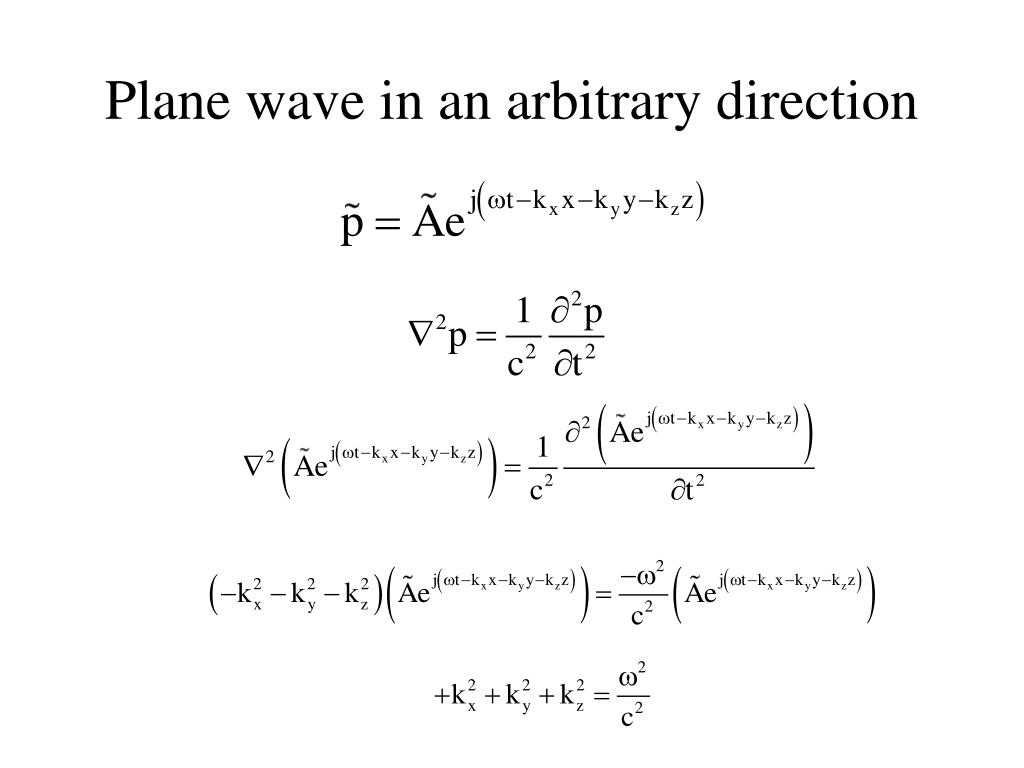

Equation

Feynman provides a derivation of the wave equation for sound in three dimensions as

where is the Laplace operator, is the acoustic pressure (the local deviation from the ambient pressure), and is the speed of sound.

A similar looking wave equation but for the vector field particle velocity is given by

- .

In some situations, it is more convenient to solve the wave equation for an abstract scalar field velocity potential which has the form

and then derive the physical quantities particle velocity and acoustic pressure by the equations (or definition, in the case of particle velocity):

- ,

- .

Solution

The following solutions are obtained by separation of variables in different coordinate systems. They are phasor solutions, that is they have an implicit time-dependence factor of where is the angular frequency. The explicit time dependence is given by

Here is the wave number.

Cartesian coordinates

- .

Cylindrical coordinates

- .

where the asymptotic approximations to the Hankel functions, when , are

- .

Spherical coordinates

- .

Depending on the chosen Fourier convention, one of these represents an outward travelling wave and the other a nonphysical inward travelling wave. The inward travelling solution wave is only nonphysical because of the singularity that occurs at r=0; inward travelling waves do exist.

See also

- Acoustics

- Acoustic attenuation

- Acoustic theory

- Differential equations

- Fluid dynamics

- Ideal gas law

- Madelung equations

- One-way wave equation

- Pressure

- Thermodynamics

- Wave equation

Notes

References

- LeVeque, Randall J. (2002). Finite Volume Methods for Hyperbolic Problems. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511791253. ISBN 978-0-521-81087-6.